Keeping up with The Scholarly Literature is a wild academic fantasy, even for those with a neatly bounded subject area. When I was a kid I thought the expression “trying to shovel a waterfall” was hilarious. As I got older I realized it was a pretty good job description for interdisciplinary scholars.

I can’t keep you up to date on everything that’s New and Now in the areas that intersect with archaeology and horror, but I can put a spotlight on works across subjects like Literature, Film Studies, and Horror Studies that I think are, if not foundational, than at least enrich our engagement and understanding or are just good nerdy fun to read.

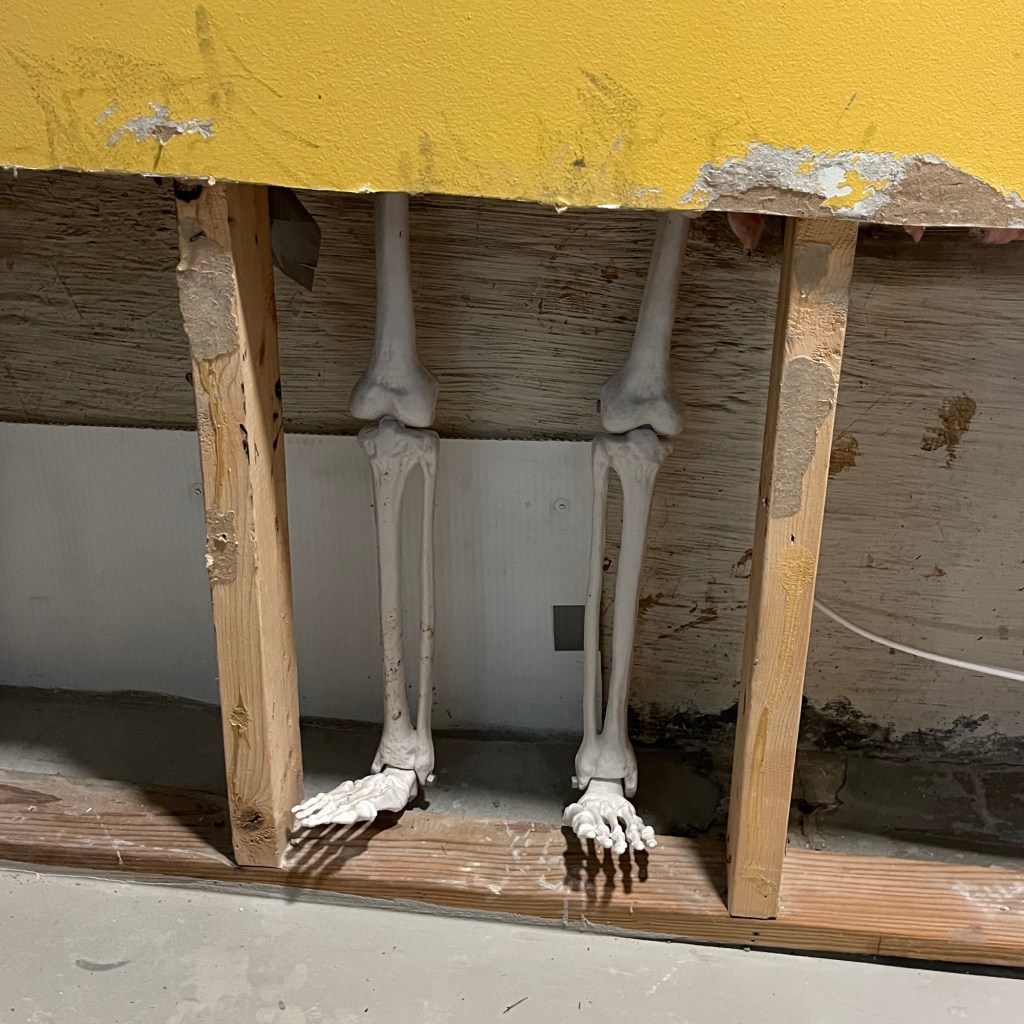

I just deleted an introductory post that had a ridiculously elaborate schema I once upon a time intended to follow here to build an annotated bibliography because Past Me was blissfully ignorant of the host of bonkers Life Stuff waiting in the wings, which has included rebuilding a partially flooded house. I also came to my senses and remembered that perfect is the enemy of fun. (That’s how that goes, right?) Past Me does wish for a gold star for not bricking up plastic skeletons in the new walls as a gift for a future homeowner, but it’s been suggested to me that this is not a thing for which most people need to be rewarded. Anyway.

I suppose “the things we find buried in the walls” is a good a transition to the topic of this post, which is actually Teresa A. Goddu’s book Gothic America: Narrative, History, and Nation (Columbia UP, 1997).

In the time it took me to write that introduction, 3 more scholars probably cited Goddu’s book. You know why? Because this book is the shit. It’s clearly written and the analysis flows from a well-developed argument that this is an appraisal of American Gothic literature as a mode with its own history and purpose, rather than a pale imitation of British or European Gothic minus the crumbling castles and inbred nobility.

Keeping it simple, here are some of the basic elements which characterize Gothic fiction. It’s not a checklist or a set of rules, just a set of qualities that work together to produce the sense of creeping dread or fear that we know when we see or hear or read it.

Setting: Most broadly, the story is set in a place that is foreboding or invokes dread. It is often decaying or falling to ruin and contains subterranean and/or confining, claustrophobic spaces. Darkness, shadow, fogs, steam, or other natural or unnatural elements increase the sense of dread and frustrate the characters (and our) ability to see the bigger picture. While medieval castles are the obvious choice, the Nostromo, the spaceship in Alien (1979), is a great example of a Gothic setting that requires neither Europe nor Earth to be effective.1

Pyramids, archaeological ruins, dense forests or jungles, and the depths of the ocean have also been put to effective use in Gothic stories.

Isolation, entrapment, or danger: Often, this is a damsel in distress. The Gothic is a particularly effective mode for exploring the ways patriarchal systems oppress and isolate women.

Decay: Decaying structures are pretty on-the-nose. Decay, like the dissolution or transgression of boundaries, can also apply to the mental status of the protagonist. Is the situation they find themself in causing them to become paranoid or mentally ill? Or is their mental deterioration what has set the story in motion? The boundaries in question can be literal or figurative. They may take the form of physical structures, territorial boundaries, ecological conditions, or the physical or mental state of the body.

Fictional archaeologists, antiquarians, and adventurers rarely meet an ethical boundary or cultural or social norm they can’t transgress on their way to knowledge and/or treasure, and those actions return to haunt them in all kinds of ways.

Supernatural elements: Sometimes, there are ghosts or monsters. Other times, there are rational explanations from the bumps in the night and the wailing in the distance, particularly in stories in which a conniving and dangerous older man is manipulating events to either drive a wealthy, lonely young heiress insane or convince everyone else that she’s mad so she can be safely locked away.

Doomed inheritances: inherited wealth, family heirlooms, curses, genetics, a shoe found buried behind the barn, or a museum full of looted artifacts are among the many ways in which the past may arrive to haunt characters in the present.

While not all Gothic tales are explicitly Horror and not all Horror is Gothic, that is a set of distinctions and discussions for another time and another place. My point is, if find yourself identifying with too many of these you may wish to invest in some glamorous white nightclothes in the event you must run breathlessly from crumbling ruins late at night.

No, that wasn’t my point at all (but you should still maybe consider doing some shopping while you still can).

My point is I wanted to lay out a general idea of what qualities Gothic works contain and how flexible they are for telling stories in which the past and the present come into conflict through the actions of humans, and how these situations can literally or figuratively haunt a person, a society, or a place for generations. 2

So. That was a long walk to get to the topic of this post, but here we are, at long last. Dr. Teresa Goddu is a Professor of English and Director of Climate and Environmental Studies at Vanderbilt University. In 1997 she published this book & the description on the publisher’s homepage is succinct yet comprehensive so I’m not going to reinvent the wheel writing my own summary because I think I’ve already said enough here today:

The gothic novel -the literary stronghold of ghosts, family curses, imperiled heroines and cumbersome plots- might be thought to fall under the category of “escapist fiction.” But in this groundbreaking reappraisal, Teresa Goddu demonstrates that the American Gothic novel was, in often surprising ways, actively engaged with social, political, and cultural concerns of its time.

Although social dislocations such as slavery or the massacre of Native Americans were repressed by our national conciousness, Goddu points out that these subjects were effectively incorporated by the gothic novel, articulated into an enduring national identity.

Focusing on literature between the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, Gothic America traces the development of the genre as a whole and of several subgenres -the female gothic, the Southern gothic, and the African-American gothic. Among the works Goddu reexamines are Poe’s Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym, Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables and The Blithedale Romance, Alcott’s ghost stories, and Jacobs’ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. It is, finally, the African-American gothic that illuminates most clearly the link between frightening literature and a horror-filled social reality.

Questioning basic assumptions about America’s identity, Gothic America is a fresh examination of both a much-neglected genre of American literature and the complex historical circumstances that produced it. [Columbia University Press]

Sadly, as the United States continues to regress socially, work like Goddu’s which lays bare how deeply intwined racism and oppression are with American cultural identity and nationalism, becomes more relevant than ever.

I think it’s important to clarify that I’m not arguing that work on the American Gothic either began or ended with Goddu’s book. That said, a significant body of work on the American Gothic has followed and I’ll be highlighting some of my favorites in forthcoming posts, as well as monographs, collections, and articles on other Gothic modes relevant to archaeological horror.

(spoiler alert: it’s all relevant)

Additionally, I want to note that Goddu’s work didn’t grind to a halt in 1997 and her recent work on intersections of climate justice and racial justice in the American South may be of particular interest to environmental anthropologists and archaeologists.

- While Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) is a nice example of Gothic but make it SciFi, the franchise does introduce archaeology in the prequels and hold onto your butts because I’ve got a lot to say about that. Just not today. ↩︎

- I get it that not everyone is here for the academic nerdery, and that’s totally cool. But I have little patience for blogs (or any writing) that throws around genre terms without offering some definitions. I don’t even care if the definition is a common or accepted one, I just want to be on the same page so I can understand the discussion. I also have no use for writers who don’t provide definitions because they’re gatekeeping – please leave me a comment or message me if I’m using a term without providing a definition or if the definition I provide seems strange. ↩︎